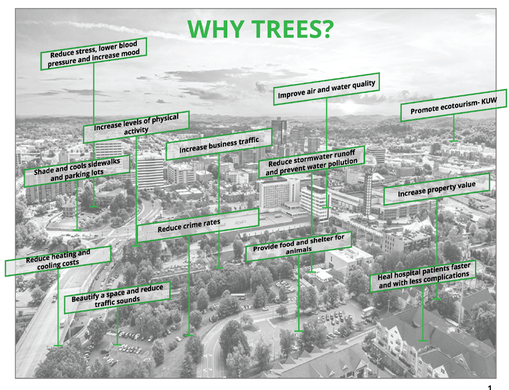

Role of Trees in Knoxville

Why all this planning and effort for trees? Is this the best use of our time? Consider the role trees play in Knoxville (and in every city):

Walkable Communities

Tree canopy cover is vital to a walkable community. According to the Federal Highway Administration, urban tree canopy along streets have been shown to slow traffic, helping ensure safe, walkable streets in communities The buffers between walking areas and driving lanes created by trees also make streets feel safer for pedestrians and cyclists.(U.S. Department of Transportation 2015). Driver stress levels have also been reported to be lower on tree-lined streets, contributing to a reduction in road rage and aggressive driving (Wolf 1998a, Kuo and Sullivan 2001).

Energy Savings

Trees provide energy savings by reducing cooling and heating costs, both through their shade as well as the release of moisture through transpiration. Trees properly placed around buildings can reduce air conditioning needs by 30% and can save 20–50% in energy used for heating. Computer models devised by the U.S. Department of Energy (2018) predict that the proper placement of only three trees can save an average household between $100 and $250 in energy costs annually. Even properties not directly adjacent to greenspaces can experience energy saving benefits from trees, with buildings 500 feet away from park spaces still experiencing significant cooling effects in summer, reducing the demand for cooling energy consumption by 43% (Toparlar et al. 2020).

This is especially important in low income communities, where household have a higher energy burden (larger percentage of monthly budget is spent on energy).

This is especially important in low income communities, where household have a higher energy burden (larger percentage of monthly budget is spent on energy).

Carbon Storage

Trees are constantly removing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Most of the carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere comes from human activities that involve the burning of fossil fuels. High levels of CO2 result in climate change, which has resulted in more frequent and severe storms, droughts, and other natural stresses across the world in recent decades. An average tree in the United States can capture about 1,200 pounds of carbon dioxide per over its lifetime; the cumulative effect of all US trees results in capturing 17% of our nation’s carbon dioxide emissions annually (Daley 2022).

Successful Business Districts

In multiple studies, consumers showed a willingness to pay 11% more for goods and shopped for a longer period of time in shaded and landscaped business districts (Wolf 1998b, 1999, and 2003). Consumers also felt that the quality of products was better in business districts surrounded by trees and were willing to pay more (Wolf 1998a).

Property Value

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that the presence of street trees increases adjacent home values by an average of $9,000 (Donovan & Butry 2010).

Wildlife Habitat / Ecosystem Health

As smaller forests are connected through planned or informal urban greenways, trees provide essential habitat to a range of birds, pollinators, and other wildlife that feed on insects (Dolan 2015). Recent studies show that bees in areas with higher tree canopy have lower levels of toxins related to pollution (Barbosa et al. 2021), and trees can be an essential source of early pollen for these important pollinators (Honchar & Gnatiuk 2020). Higher density (and diversity) of trees is also associated with higher bird density, including natives and rare birds of prey (Heggie-Gracie et al. 2020 & Mirski 2020).

Associated with Lower Crime

Trees have been shown to contribute to a decrease in crime. A study in Baltimore found that a 10% increase in tree canopy was associated with a roughly 12% decrease in crime (Troy et al. 2012). In an experimental study, newly planted street trees were strongly correlated with a reduction in violent crimes, an effect especially prominent in neighborhoods with lower median household income (Burley 2018).

References

American Lung Association (ALA). 2015. State of the Air 2015. http://www.stateoftheair.org (accessed May 30, 2015).

Astrell-Burt, T., Feng, X. 2019. Does sleep grow on trees? A longitudinal study to investigate potential prevention of insufficient sleep with different types of urban green space. SSM - Population Health https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352827319301703

Barbosa, M., Fernandes, A.C.C., Alvez, R.S.C., Alves, D.A., et al. 2021. Effects of native forest and human-modified land covers on the accumulation of toxic metals and metalloids in the tropical bee Tetragonisca angustala. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 215: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112147

Becker, D.A., Browning, M., Kuo, M., Van Den Eeden, S.K. 2019. Is green land cover associated with less health care spending? Promising findings from county-level Medicare spending in the continental United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 41: 39-47.

Burden, D. 2008. "22 Benefits of Urban Street Trees." Walkable Communities, Inc. http://www.walkable.org/assets/downloads/22BenefitsofUrbanStreetTrees.pdf. Accessed March 2015.

Burley, B.A. (2018) Green infrastructure and violence: Do new street trees mitigate violent crime? Health & Place 54, 43-49

Coville, R.C., Kruegler, J., Selbig, W.R., Hirabayashi, S., Loheide, S.P., Avery, W., Shuster, W. et al. 2022. Loss of street trees predicted to cause 6000 L/tree increase in leaf-on stormwater runoff for Great Lakes urban sewershed. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 74: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127649

Daley, J. 2022. Trees are the secret weapon of America's historic climate bill. Time https://time.com/6208895/climate-bill-forests/ Accessed March 7, 2023.

Dolan, RW. 2015. Two Hundred Year of Forest Change: Effects of Urbanization on Tree Species Composition and Structure. ISA Aboriculture & Urban Forestry 41 (3): 136-145

Donovan, G.H., & Butry, D.T. 2010. Trees in the city: valuing street trees in Portland, Oregon. Landscape and Urban Planning 94: 77-83

EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Heat Island Effect: Trees and Vegetation. http://www.epa.gov/heatislands/mitigation/trees.htm. Accessed May 30, 2015.

Heggie-Gracie, S.D., Krull, C.R., & Stanley, M.C. 2020. Urban divide: predictors of bird communities in forest fragments and the surrounding urban matrix. Emu - Austral Ornithology: https://doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2020.1857650.

Honchar, G.Y. & Gnatiuk, A.M. 2020. Urban ornamental plants for sustenance of wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Plant Introduction 85: https://doi.org/10.46341/PI2020014

Kuo, F., and W. Sullivan. 2001. Aggression and Violence in the Inner City: Effects of Environment via Mental Fatigue. Environment and Behavior 33(4):543–571.

Lovasi, G.S., Quinn, J.W., Neckerman, K.M., Perzanowski, M.S., & Rundle, A. 2008. Children Living in Areas with More Street Trees have Lower Prevalence of Asthma. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 62:7(647-49).

Maher, B.A., Ahmed, I.A.M., Davison, B., Karloukovski, V. & Clarke, R. 2013. Impact of roadside tree lines on indoor concentrations of traffic-derived particulate matter. Environmental Science & Technology 47(23): 13737-13744. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/es404363m

Mirski, P. 2020. Tree cover density attracts rare bird of preay specialist to nest in urban forest. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 55: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126836

North Carolina State University. 2012. Americans are Planting Trees of Strength. http://www.treesofstrength.org/benefits.htm. Accessed May 15, 2015.

Ponte, S., Sonti, N.F., Phillips, T.H., & Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. 2021. Transpiration rates of red maple (Acer rubrum L.) differ between management contexts in urban forests of Maryland, USA. Scientific Reports 11: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-01804-3

Rajoo, K.S., Karam, D.S., Abdu, A, Rosli, Z., Gerusu, G.J. 2021. Addressing psychosocial issues caused by the COVID-19 lockdown: Can urban greeneries help? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127340

Seitz, J. and F. Escobedo. 2008. Urban Forests in Florida: Trees Control Stormwater Runoff and Improve Water Quality. School of Forest Resources and Conservation Department, UF/IFAS Extension. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fr239. Accessed November 3, 2015.

Sivarajah, S., Smith, S.M. & Thomas, S.C. 2018. Tree cover and species composition effects on academic performance of primary school students. PLoS ONE 13(12): e0193254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193254

Toparlar, Y., Blocken, B., Maiheu, B., & van Heijst, G. 2020. More than a green space: how much energy can an urban park save? Production of Climate Responsive Urban Built Environments, proceedings book 2: 23-32.

Troy, A., Grove, J.M., O'Neil-Dunne, J. 2012. The relationship between tree canopy and crime rates across an urban-rural gradient in the greater Baltimore region. Landscape and Urban Planning 106(3): 262-270.

Ulmer, J.M., Wolf, K.L., Backman, D.R., Tretheway, R.L., Blain, C.J., O'Neil-Dunne, J.P., & Frank, L.D. 2016. Multiple health benefits of urban tree canopy: The mounting evidence for green prescription. Health & Place 42: 54-62.

US DOE - Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. 2018. Low-Income Household Energy Burden Varies Among States — Efficiency Can Help In All of Them. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/01/f58/WIP-Energy-Burden_final.pdf

Van Den Eeden, S.K., Browning, M.H., Becker, D.A., Shan, J., Alexeeff, S.E., Ray, G. T., Quesenberry, C.P., Kuo, M. 2022. Association between residential green cover and direct healthcare costs in Northern California: An individual level analysis of 5 million persons. Environment International 164: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107174 Accessed October 5, 2022.

Wolf, K.L. 1998a. Urban Nature Benefits: Psycho-Social Dimensions of People and Plants. University of Washington, College of Forest Resources Fact Sheet. 1(November).

Wolf, K.L. 1998b. Trees in Business Districts: Comparing Values of Consumers and Business. University of Washington College of Forest Resources Fact Sheet. 4(November).

Wolf, K.L. 1999. Grow for the Gold. TreeLink Washington DNR Community Forestry Program. 14(spring).

Wolf, K.L. 2003. Public Response to the Urban Forest in Inner-City Business Districts. J. Arbor 29(3):117–126.

US DOT, FHWA. 2015. Bicycle & Pedestrian Planning: Best Practices Design Guide. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/sidewalk2/sidewalks209.cfm. Accessed January 3, 2020.

Yu, Chia-Pin & Hsieh, Hsuan 2020. Beyond restorative benefits: evaluating the effect of forest therapy on creativity. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 51: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126670

Astrell-Burt, T., Feng, X. 2019. Does sleep grow on trees? A longitudinal study to investigate potential prevention of insufficient sleep with different types of urban green space. SSM - Population Health https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352827319301703

Barbosa, M., Fernandes, A.C.C., Alvez, R.S.C., Alves, D.A., et al. 2021. Effects of native forest and human-modified land covers on the accumulation of toxic metals and metalloids in the tropical bee Tetragonisca angustala. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 215: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112147

Becker, D.A., Browning, M., Kuo, M., Van Den Eeden, S.K. 2019. Is green land cover associated with less health care spending? Promising findings from county-level Medicare spending in the continental United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 41: 39-47.

Burden, D. 2008. "22 Benefits of Urban Street Trees." Walkable Communities, Inc. http://www.walkable.org/assets/downloads/22BenefitsofUrbanStreetTrees.pdf. Accessed March 2015.

Burley, B.A. (2018) Green infrastructure and violence: Do new street trees mitigate violent crime? Health & Place 54, 43-49

Coville, R.C., Kruegler, J., Selbig, W.R., Hirabayashi, S., Loheide, S.P., Avery, W., Shuster, W. et al. 2022. Loss of street trees predicted to cause 6000 L/tree increase in leaf-on stormwater runoff for Great Lakes urban sewershed. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 74: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127649

Daley, J. 2022. Trees are the secret weapon of America's historic climate bill. Time https://time.com/6208895/climate-bill-forests/ Accessed March 7, 2023.

Dolan, RW. 2015. Two Hundred Year of Forest Change: Effects of Urbanization on Tree Species Composition and Structure. ISA Aboriculture & Urban Forestry 41 (3): 136-145

Donovan, G.H., & Butry, D.T. 2010. Trees in the city: valuing street trees in Portland, Oregon. Landscape and Urban Planning 94: 77-83

EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Heat Island Effect: Trees and Vegetation. http://www.epa.gov/heatislands/mitigation/trees.htm. Accessed May 30, 2015.

Heggie-Gracie, S.D., Krull, C.R., & Stanley, M.C. 2020. Urban divide: predictors of bird communities in forest fragments and the surrounding urban matrix. Emu - Austral Ornithology: https://doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2020.1857650.

Honchar, G.Y. & Gnatiuk, A.M. 2020. Urban ornamental plants for sustenance of wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Plant Introduction 85: https://doi.org/10.46341/PI2020014

Kuo, F., and W. Sullivan. 2001. Aggression and Violence in the Inner City: Effects of Environment via Mental Fatigue. Environment and Behavior 33(4):543–571.

Lovasi, G.S., Quinn, J.W., Neckerman, K.M., Perzanowski, M.S., & Rundle, A. 2008. Children Living in Areas with More Street Trees have Lower Prevalence of Asthma. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 62:7(647-49).

Maher, B.A., Ahmed, I.A.M., Davison, B., Karloukovski, V. & Clarke, R. 2013. Impact of roadside tree lines on indoor concentrations of traffic-derived particulate matter. Environmental Science & Technology 47(23): 13737-13744. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/es404363m

Mirski, P. 2020. Tree cover density attracts rare bird of preay specialist to nest in urban forest. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 55: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126836

North Carolina State University. 2012. Americans are Planting Trees of Strength. http://www.treesofstrength.org/benefits.htm. Accessed May 15, 2015.

Ponte, S., Sonti, N.F., Phillips, T.H., & Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. 2021. Transpiration rates of red maple (Acer rubrum L.) differ between management contexts in urban forests of Maryland, USA. Scientific Reports 11: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-01804-3

Rajoo, K.S., Karam, D.S., Abdu, A, Rosli, Z., Gerusu, G.J. 2021. Addressing psychosocial issues caused by the COVID-19 lockdown: Can urban greeneries help? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127340

Seitz, J. and F. Escobedo. 2008. Urban Forests in Florida: Trees Control Stormwater Runoff and Improve Water Quality. School of Forest Resources and Conservation Department, UF/IFAS Extension. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fr239. Accessed November 3, 2015.

Sivarajah, S., Smith, S.M. & Thomas, S.C. 2018. Tree cover and species composition effects on academic performance of primary school students. PLoS ONE 13(12): e0193254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193254

Toparlar, Y., Blocken, B., Maiheu, B., & van Heijst, G. 2020. More than a green space: how much energy can an urban park save? Production of Climate Responsive Urban Built Environments, proceedings book 2: 23-32.

Troy, A., Grove, J.M., O'Neil-Dunne, J. 2012. The relationship between tree canopy and crime rates across an urban-rural gradient in the greater Baltimore region. Landscape and Urban Planning 106(3): 262-270.

Ulmer, J.M., Wolf, K.L., Backman, D.R., Tretheway, R.L., Blain, C.J., O'Neil-Dunne, J.P., & Frank, L.D. 2016. Multiple health benefits of urban tree canopy: The mounting evidence for green prescription. Health & Place 42: 54-62.

US DOE - Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. 2018. Low-Income Household Energy Burden Varies Among States — Efficiency Can Help In All of Them. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/01/f58/WIP-Energy-Burden_final.pdf

Van Den Eeden, S.K., Browning, M.H., Becker, D.A., Shan, J., Alexeeff, S.E., Ray, G. T., Quesenberry, C.P., Kuo, M. 2022. Association between residential green cover and direct healthcare costs in Northern California: An individual level analysis of 5 million persons. Environment International 164: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107174 Accessed October 5, 2022.

Wolf, K.L. 1998a. Urban Nature Benefits: Psycho-Social Dimensions of People and Plants. University of Washington, College of Forest Resources Fact Sheet. 1(November).

Wolf, K.L. 1998b. Trees in Business Districts: Comparing Values of Consumers and Business. University of Washington College of Forest Resources Fact Sheet. 4(November).

Wolf, K.L. 1999. Grow for the Gold. TreeLink Washington DNR Community Forestry Program. 14(spring).

Wolf, K.L. 2003. Public Response to the Urban Forest in Inner-City Business Districts. J. Arbor 29(3):117–126.

US DOT, FHWA. 2015. Bicycle & Pedestrian Planning: Best Practices Design Guide. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/sidewalk2/sidewalks209.cfm. Accessed January 3, 2020.

Yu, Chia-Pin & Hsieh, Hsuan 2020. Beyond restorative benefits: evaluating the effect of forest therapy on creativity. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 51: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126670